10.1 Curves Defined by Parametric Equations #

- Parametric equations are written as .$(f(t), g(t))$

- They define curves (not functions!)

- Time

- .$t \in [t_i, t_f]$

- Initial point: .$\big(f(t_i), g(t_i)\big)$

- Terminal point: .$\big(f(t_f), g(t_f)\big)$

- For parametric equation in form .$\big(h + r \cdot \sin(t), k + r \cdot \cos(t)\big)$ on .$t \in [0, 2\pi]$ , the resulting curve is a circle clockwise centered around the point .$(h,k)$

- Likewise, .$(r \cdot \cos(t), r \cdot \sin(t))$ is counter clockwise

- Useful Desmos calculator

- If we need to graph an equation in form .$x = g(y)$ , we can use parametric equations .$x = g(t)$ and .$y = t$

10.2 Calculus with Parametric Curves #

Tangents #

- Given .$x = f(t)$ and .$y = g(t)$ where both .$f$ and .$g$ are differentiable, we can get the tangent line to the curve by finding .$\frac{dy}{dx}$

- We can find .$\frac{dy}{dt}$ using the chain rule: $$\frac{dy}{dx} \cdot \frac{dx}{dt}$$

- If .$\frac{dx}{dt} \neq 0$ , then we can solve .$\frac{dy}{dt}$ : $$\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{\frac{dy}{dt}}{\frac{dx}{dt}}$$

- Horizontal tangents exist when .$\frac{dy}{dt}= 0$ (assuming .$\frac{dx}{dt} \neq 0$ )

- Vertical tangents exist when .$\frac{dx}{dt}= 0$ (assuming .$\frac{dy}{dt} \neq 0$ )

Double Derivative #

$$\frac{d^2y}{dx^2} = \frac{d}{dx}\Big(\frac{dy}{dx}\Big) = \frac{d}{dt}\cdot\frac{dt}{dx}\Big(\frac{dy}{dx}\Big) = \frac{\frac{d}{dt}\Big(\frac{dy}{dx}\Big)}{\frac{dx}{dt}}$$

Areas #

Given .$x = f(t)$ and .$y = g(t)$ over .$t \in (\alpha, \beta)$ , we can calculate the area between .$C$ and the .$x$ -axis with the following equation $$A = \int_\alpha^\beta f’(t) \cdot g(t)\ dt $$ Likewise, between .$C$ and the .$y$-axis we derive the parametric equation for .$y$ : $$A = \int_\alpha^\beta f(t) \cdot g’(t)\ dt $$

Arc Length #

To find length .$L$ of curve .$C$ given in form .$x = f(t)$ and .$y = g(t)$ on .$t \in [\alpha, \beta]$ where .$\frac{dx}{dt} = f’(t) > 0$ (meaning that .$C$ is traversed once from left to right as .$t$ increases from .$\alpha$ to .$\beta$ ) and where .$f’$ and .$g’$ are continuous on .$[\alpha, \beta]$ : $$L = \int_\alpha^\beta \sqrt{\Big(\frac{dx}{dt}\Big)^2 + \Big(\frac{dy}{dt}\Big)^2}\ dt$$ Note that trig functions (.$\sin, \cos, \text{etc.})$ ) loop every .$\frac{\pi}{2}$ because of the formula finds the absolute value.

Surface Area #

Suppose the curve .$C$ given the equations .$x = f(t)$ and .$y = g(t)$ on .$\ t \in [\alpha, \beta]$ where .$f’$ and .$g’$ are continuous, and .$g(t) > 0$ , is rotated about the .$x$ -axis. If .$C$ is traversed exactly once, then the area of the resulting surface is given by $$S = 2\pi \int_\alpha^\beta y(t) \sqrt{\Big(\frac{dx}{dt}\Big)^2 + \Big(\frac{dy}{dt}\Big)^2}\ dt$$ Similarly, if instead .$C$ is rotated about the .$y$ -axis instead we use the following: $$S = 2\pi \int_\alpha^\beta x(t) \sqrt{\Big(\frac{dx}{dt}\Big)^2 + \Big(\frac{dy}{dt}\Big)^2}\ dt$$

10.3 Polar Coordinates #

- Pole = origin; labeled .$O$

- Polar axis = line through .$O$

- Polar coordinates = .$r, \theta$

- .$r$ is distance from point .$P$ and .$O$

- .$\theta$ is the angle between the polar axis and the line .$OP$

- .$(r, \theta) = (-r, \theta + \pi)$

Converting between Cartesian #

- .$x = r\cdot \cos\theta$

- .$y = r\cdot \sin\theta$

- .$r^2 = x^2 + y^2$

- .$\tan\theta = \frac{y}{x}$

Symmetry #

- If polar equation is the same when .$\theta = -\theta$ , the curve is symmetric about the polar axis

- If polar equation is the same when .$r = -r$ or when .$\theta = \theta + \pi$ , the curve is symmetric about the pole

- If polar equation is the same when .$\theta = \pi-\theta$ , then the curve is symmetric about the vertical line .$\theta = \pi/2$

Polar Tangents #

Knowing that $$x = r \cdot \cos\theta = f(\theta)\cdot\cos\theta$$ $$y = r \cdot \sin\theta = g(\theta)\cdot\sin\theta$$ We can use the product rule to find the tangent equation $$\frac{dy}{dx} = \frac{\frac{dy}{d\theta}}{\frac{dx}{d\theta}} = \frac{\frac{dr}{d\theta} \sin\theta + r\cos\theta}{\frac{dr}{d\theta}\cos\theta - r \sin\theta} $$

- Horizontal Tangent: .$\frac{dy}{d\theta} = 0$ (when .$\frac{dx}{d\theta} \neq 0$ )

- Vertical Tangent: .$\frac{dx}{d\theta} = 0$ (when .$\frac{dy}{d\theta} \neq 0$ )

- Notice that for .$r = 0$ , then .$\frac{dy}{dx} = \tan\theta$ if .$\frac{dr}{d\theta} \neq 0$ We can then write the full formula: $$y-y_0 = \frac{dy}{dx}\Big(\theta\Big)(x-x_0)$$

10.4 Area and Lengths in Polar Coordinates #

Area of Polar Region #

Knowing that the area of a “slice” can be written as .$A = \frac{1}{2}r^2\theta$ , we can expand this to the case where the curve is a function .$r = f(\theta)$ : $$A = \int_a^b \frac{1}{2} r^2\ d\theta$$

Arc Length of Polar Curve #

Given a polar curve .$r = f(\theta), a \leq \theta \leq b$ , we can re-write our base equations as $$x = r\cos\theta = f(\theta)\cos\theta$$ $$y = r\sin\theta = f(\theta)\sin\theta$$ Thus we can use the product rule when differentiating to get $$\frac{dx}{d\theta} = \frac{dr}{d\theta}\cos\theta - r\sin\theta$$ $$\frac{dy}{d\theta} = \frac{dr}{d\theta}\sin\theta + r\cos\theta$$ and using .$\cos^2\theta + \sin^2\theta = 1$ , we have $$\Big(\frac{dx}{d\theta}\Big)^2 + \Big(\frac{dy}{d\theta}\Big)^2 = [\text{ugly stuff, see page 711}] = \Big(\frac{dr}{d\theta}\Big)^2 + r^2$$ so when .$f’$ is continuous, we can write the arc length equation as $$L = \int_a^b \sqrt{\Big(\frac{dx}{d\theta}\Big)^2 + \Big(\frac{dy}{d\theta}\Big)^2} d\theta = \int_a^b \sqrt{r^2 + \Big(\frac{dr}{d\theta}\Big)^2}d\theta$$

Common shapes #

Rose #

$$a\cdot[\sin \text{or} \cos](k\cdot\theta)$$

$$a\cdot[\sin \text{or} \cos](k\cdot\theta)$$

- .$r$ = .$a$

- .$\sin$ = Symmetry over .$\theta = 0$

- .$\cos$ = Symmetry over .$\theta = \pi/2$

- If .$k$ is even, rose will have .$2k$ petals.

- If .$k$ is odd, rose will have .$k$ petals.

- .$T = 2\pi/k$ is range of a petal’s cycle

- .$2\pi/T = k$ cycles displayed in graph

- .$A_{\text{petal}} = \frac{\pi a^2}{4k}$

Cardioid #

$$r(\theta) = a(1-\cos\theta)$$

$$A = \frac{3}{2}\pi a^2$$

$$L = 8a$$

$$r(\theta) = a(1-\cos\theta)$$

$$A = \frac{3}{2}\pi a^2$$

$$L = 8a$$

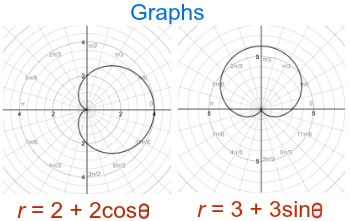

Limaçon #

$$r = b+a\cos\theta$$

Other equations I’m too lazy to type out

$$r = b+a\cos\theta$$

Other equations I’m too lazy to type out