03/15 Capacitors #

Structure and Physics #

See also, 7B 24

- Capacitors is a circuit element that stores charge

- Positive charges build up on the (top) surface of the plate connected to the positive terminal and negative charges build up on the (bottom) surface of the plate connected to the negative terminal.

- Capacitors have an associated quantity,

$C$apacitance (farads); the ratio of the amount of

electric charge $Q$ (coulombs) stored on a conductor to a difference in electric potential $V$

- Units: Farads, $F = \frac{C}{V}$.

- Depends on the physical geometry of a capacitor

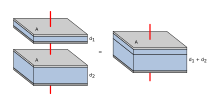

$$C = \varepsilon_0 \frac{A}{d}$$

- $A$: Area of plates

- $d$: Distance between plates

- $\varepsilon_0$: Permittivity of free space, $8.854\cdot 10^{-12} \frac{\text{F}}{\text{m}}$

A physical diagram of a capacitor, with 2 metal plates and a dielectric (commonly air) between them

- For most purposes, capacitors do not have polarity– their orientation doesn’t impact their behavior.

- The plate that corresponds to the “+” terminal, stores $+Q = +CV$ and the plate that corresponds to the “-” terminal stores $−Q = −CV$

- The amount of charge $Q$ on a capacitor is related to its geometrical structure (capacitance $C$) and the voltage applied to it $V$:

$$Q=CV$$

- When we apply a voltage across the conductive plates, we create a potential difference, and so charges will build up on the plates

- They will not build up indefinitely because this potential difference is not infinitely strong

- At some point, an additional positive charge will be ambivalent about joining the plate; while there is a potential difference $V_+ − V_−$ between the plates attracting the charge, there are also repulsive forces from the charges that already exist on the plate

- After this amount of critical charge forms on the plate, no additional charge will enter

- Geometry

- The more the $A$rea, the more the total charge that can fit on the plate because the individual charges can spread out more, decreasing the repulsive forces

- Smaller the $d$istance between the plates, the more strongly the $+$ and $−$ charges attract each other

- That is, for the same voltage, decreasing the distance of plate separation increases the charge that will build up on the plate

Energy Storage #

When we apply a potential difference, charges build up on the plates; these charges are the reason that a capacitor stores energy. The repulsion between charges on a given plate means that moving a charge onto the plate takes energy (supplied by the voltage source). The more charge already on a plate, the more energy it takes to push another charge on.

$$V = \frac{dE}{dQ}$$ $$dE = V dQ$$ $$dE = V \cdot d (CV)$$ $$\int dE = C \int_0^V V\ dV$$ $$ \Longrightarrow E = \frac{1}{2}CV^2$$ This is the energy of a capacitor when it is fully charged, holding the complete $Q$ determined by $C$ and $V$.

$I$-$V$ Relationship and Behavior #

Current #

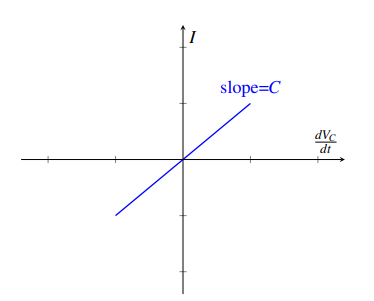

$$Q = CV$$ $$\frac{dQ}{dt} = \frac{dCV}{dt}$$ $$ \Longrightarrow I = C \frac{dV}{dt}$$

- Current is only flowing through the capacitor if the voltage across the capacitor is changing with time

- If the voltage is no longer changing, then the current through the capacitor will equal 0.

- That is, in steady state (after the current has been running for a very long time), direct current (DC) capacitors act as open circuits

- If the voltage across it is constant, then the plates are already full of charge for that voltage

- That is, any additional charge will feel the repulsive forces of the existing charges and will not want to enter the plate.

Note that the negative charges build up on the bottom plate; this happens because the positive charges on the top plate push the positive charges away from the bottom plate. This means that in reality, the charges entering the top plate are not the same exact physical charges that exit the bottom plate, but it doesn’t matter! From the perspective of the other circuit elements (and for our purposes), current flows just the same

Voltage #

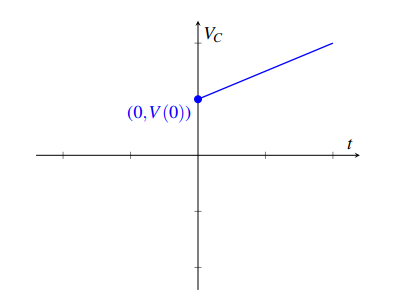

$$I = C \frac{dV}{dt}$$ $$I\ dt = C\ dV$$ $$\int I\ dt = \int_0^V C\ dV$$ $$It = C(V(t) - V(0))$$ $$V(t) = \frac{I}{C}t + V(0)$$

- To integrate the left-hand side, we assume that the current $I$ is constant wrt time.

Network Simplifications #

Full derivations start page 5

Note We can only simplify (that is, find $C_{eq}$) iff we know the starting states of each capacitor

Note: The parallel operator $\parallel$ is just a mathematical tool; it happened to describe the equivalence for resistors in parallel but the operator actually applies to capacitors in series. As with resistors in parallel, capacitors in series are best simplified pairwise; that is, for a system with capacitors in series can be simplified as $C_{eq} = C_1 \parallel C_2 = \frac{C_1 C_2}{C_1 + C_2}$Parallel #

- Parallel capacitors share terminal nodes, thus the voltage across capacitors is equal at steady state.

- Therefore, their capacitances add up: $$C_{eq} = \sum_i C_i = C_1 + \dots + C_n$$

- Intuitively, charge is apportioned among them by size.

Series #

- Series capacitors have the same current through them by KCL

- The entire series acts as a capacitor smaller than any of its components: $$\frac{1}{C_{eq}} = \sum_i \frac{1}{C_i} = \frac{1}{C_1} + \dots + \frac{1}{C_n}$$

- Intuitively, the separation distance, rather than plate area, adds up

- The inner middle two plates carry equal and opposite amounts of charge, so their net contribution to charge storage is $0$

- If all initially uncharged, the charge across all are equal to each other at steady state

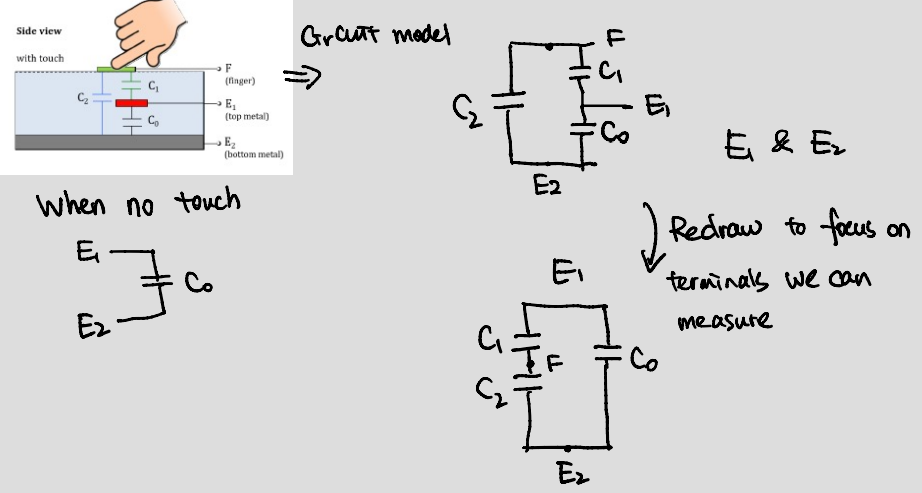

03/18 Capacitive Touchscreen #

- When there is touch, we form a capacitor

It is worth noting that there is capacitance everywhere because everything is a conductor (to some extent). There is capacitance between your fingers and your laptop keys, your fingers and our phone, and (to a much lesser extent) you and Pluto!

Measuring $V$ or $I$ #

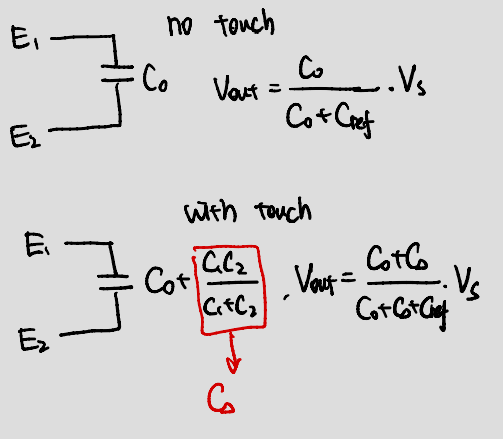

- When we have no touch, we have an open circuit so we only have $C_0$

- When we do touch, we close the circuit so $C_1$ and $C_2$ both begin charging: $$C_0 + C_1 \parallel C_2$$ $$C_0 + \frac{C_1 C_2}{C_1 + C_2}$$ $$C_0 + \Delta C$$ $$C_0 + C_{eq}$$

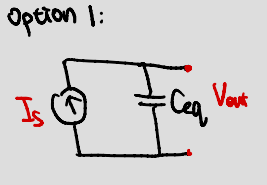

DC #

- Assuming $V_{out}(0) = 0$ $$I_S = C_{eq} \frac{d V_{out}(t)}{dt}$$ $$V_{out} = \int_0^t \frac{I_S}{C_{eq}}dt$$ $$\dots = \frac{I_S t }{C_{eq}}$$ $$ \Longrightarrow C_{eq} = \frac{I_S t}{V_{out}} $$

Downside:

Downside:

- $V_C$ will grow to infinity

- Can’t to build a current source easily

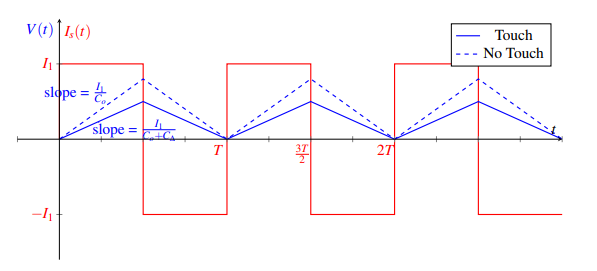

AC #

- If we replace our regular direct current (DC) source with an alternating current (AC) source then we don’t have to worry about $V_C \to \infty$

$$V_C(t) = \begin{cases}

\frac{I}{C}t & t \in \gamma [0, \frac{T}{2}) \\

-\frac{I}{C}(t- \frac{T}{2}) + \frac{I}{C} \frac{T}{2} & t \in \gamma [\frac{T}{2}, T) \\

\end{cases}; \gamma \in \mathbb{Z^+}$$

Measuring $\Delta C$ #

We can’t measure capacitance directly, but if we can transform capacitance into a voltage, we can measure that.

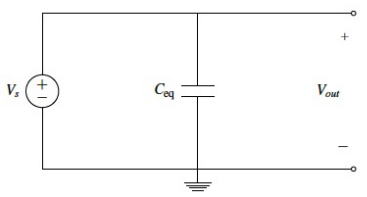

Attempt 1 #

Doesn’t work: $V_{out} = V_s$ regardless of if there is a touch or not

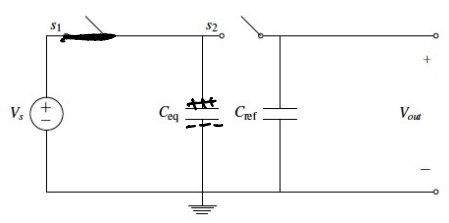

Attempt 2 #

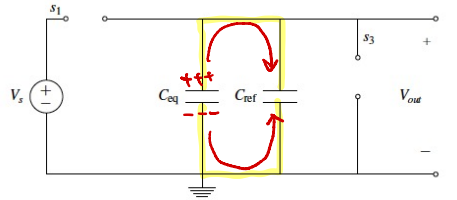

Phase 1 ($\phi_1$): Close $s_1$, open $s_2$

$$Q_{eq} = C_{eq} V_S $$

Phase 2 ($\phi_2$): Close $s_2$, open $s_1$

- Results in Charge sharing causing unknown/ambiguous initial conditions

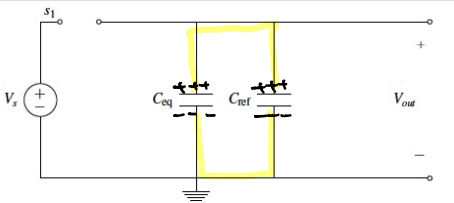

Attempt 3 #

Phase 1 ($\phi_1$): Close $s_1, s_3$, open $s_2$

- $C_{eq}$ charges: $Q_{eq} = C_{eq} V_S$

- $C_{ref}$ discharges: $Q_{ref} = C_{ref} V_{out} = 0$

$$Q_{\phi 1} = C_{eq} \cdot V_S$$

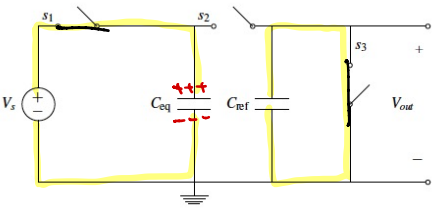

By conservation of charge $$Q_{\phi 1} = Q_{\phi 2}$$ $$C_{eq} \cdot V_S = C_{eq} \cdot V_{out} + C_{ref} \cdot V_{out}$$ $$ \therefore V_{out} = \frac{C_{eq}}{C_{eq} + C_{ref}} V_S$$ therefore, when touching we change voltage!

Phase 2 ($\phi_2$): Close $s_2$, open $s_1, s_3$

- $V_{C_{eq}} = V_{out}$

- $V_{C_{ref}} = V_{out}$

$$Q_{\phi 2} = C_{eq} \cdot V_{out} + C_{ref} \cdot V_{out}$$