25.1 The Electric Battery #

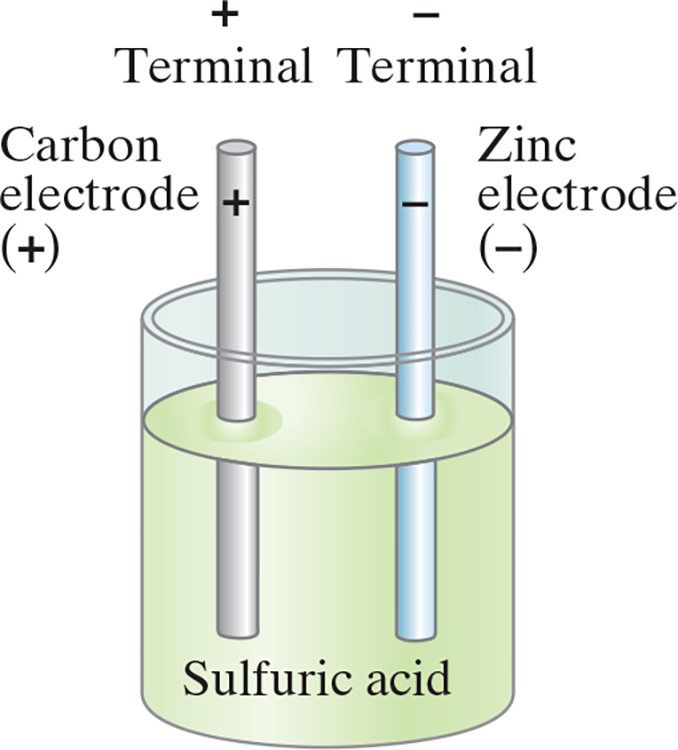

- Batteries produce electricity by transforming chemical energy into electric energy

- Simple battery (cells) contain two plates or rods of dissimilar metals called electrodes

- The portion of rods outside of the solution are called the terminals

- Anode: The positive electrode

- Cathode: The negative electrode

- These electrodes are emersed in the electrolyte: a solution such as a dilute acid

Chemical Process:

- The acid dissolve the zinc electrode, causing zinc atoms to leave two electrons behind on the electrode and enters the solution as a positive ion. The zinc electrode thus acquires a negative charge.

- Then the electrolyte becomes positively charged and can pull electrons off the carbon electrode. Thus the carbon electrode becomes positively charged.

- Because there is an opposite charge on the two electrodes, there is a potential difference between the two terminals.

- When a battery isn’t connected, only a small amount of zinc is dissolved

- The zinc electrode becomes increasingly negative

- Thus, any new positive zinc ions produced are attracted back to the electrode

- That is, if a charge is allowed to flow then the zinc can dissolve

- The voltage depends ot the electrodes’ material and their relative ability to give up electrons

25.2 Electric Current #

- When a circuit is formed, charge can move (flow) through the wires from one terminal to the other

- Any flow of charge is called an electric current

- Flow can only occur on a continuos conducting path (a complete circuit)

- If there’s any break, our circuit is called an open circuit and no current flows

- The symbol for battery is the following:

Conventional current from .$+$ to .$-$ is equivalent to a negative electron flow from .$-$ to .$+$

- Current in a wire is defined as the net amount of charge that passes through the wire’s full cross section at any point in time: $$\bar I = \frac{\Delta Q}{\Delta t} \Longrightarrow I = \frac{dQ}{dt}$$

- Current is measured in coulombs per second; ampere (amp): .$\text{1 A = 1 C/s}$

25.3 Ohm’s Law: Resistance and Resistors #

- For a current to exist, there must be a potential difference (e.g. between the terminals of a battery)

- That is, the current is proportional to the potential difference:

$$I \propto V$$

- E.x., a wire connected to a .$6V$ battery results in a current twice that of a .$3V$ battery

- The current depends on the resistance that the wires offers

- The electron flow is impeded partly due to the atoms in the wire

- .$R$ is this proportionality factor between voltage and current

- Thus, we get Ohm’s Law: $$V = IR$$

- Ohm’s law only works for when .$R$ is a constant, i.e a metal conductor

- In reality, .$R$ isn’t constant if temperature changes much

- Materials that follow Ohm’s law are labeled as “ohmic”

- Resistance has the units/notation .$\text{1 $\Omega$ = 1 V/A}$

- Resistors are used to limit/control the current in a circuit

- toolbox.mehvix.com/resistor

- As a current passes through a resistor, the charge/current stays the same but the electric potential decreases

Clarifications of Behavior

- Current’s magnitude depends on that device’s resistance

- Can be though of as the “response” to the voltage: increases if voltage increases or resistance decreases

- Current is constant – it’s energy so it cannot be destroyed by components and it’s not created by a battery

- Resistance is a property of the device/wire

- Voltage is external to the wire of device – it’s applied across the two ends of the wire

- Batteries maintain a constant potential difference – act as a source of voltage

25.4 Resistivity #

- Resistivity has experimentally been found as

$$R = \rho \frac{l}{A}$$

- .$\rho$ is the resistivity (constant of proportionality) and depends on the material

- Has units .$\Omega \cdot \text{m = V/A $\cdot $ m}$

- .$l$ is the wire length

- .$A$ is the cross-section area

- .$\rho$ is the resistivity (constant of proportionality) and depends on the material

- The reciprocal of resistivity is conductivity: .$\sigma = \rho^{-1}$

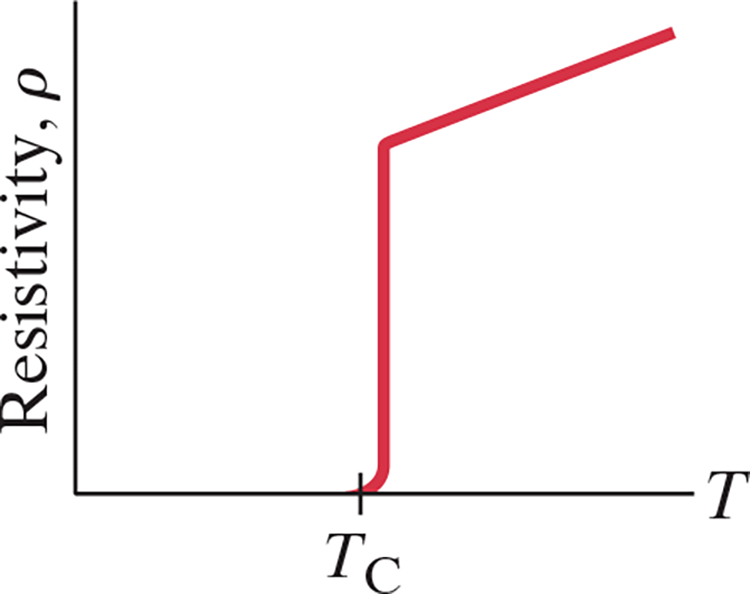

Temperature #

- Resistivity varies (generally increasing) with temperature

$$\rho_T = \rho_0 = \bigg[ 1+ \alpha (T-T_0)\bigg]$$

- .$\rho_0$ is the resistivity at some reference temperature .$T_0$ (i.e .$0^\circ \text{ C}$)

- .$\rho_T$ is the new resistivity at the current (higher) temperature .$T$

- .$\alpha$ is the temperature coefficient of resistivity that depends on material

- Note that the temperature coefficient for semiconductors can be negative.

- At higher temperatures, some of the electrons that are normally not free in a semiconductor can become free and contribute to the current.

- Thus, the resistance of a semiconductor can decrease with an increase in temperature.

25.5 Electric Power #

- Electric energy is transformed into thermal energy (and light) in stove burners, toasters, etc.

- The current creates collisions between the moving electrons and the atoms in the wire

- That is, the KE from the wire’s atoms increases meaning the temperature increases too

$$P = \frac{dU}{dt} = \frac{dq}{dt}\cdot V$$

- This is because energy is transformed when a tiny charge .$dq$ moves through a potential difference .$V$ is .$dU = V\ dq$

- The charge that flows per second, .$dq/dt$, is the electric current .$I$:

$$P = IV = I^2 R = \frac{V^2}{R}$$

- The SI unit for power is the watt: .$\text{1 W = 1 J/s}$

- We get the last two equations by plugging in .$V = IR$

25.7 Alternating Current #

- When a battery is connected to a circuit, the current moves steadily in one direction (DC: Direct Current)

- Electric generators at power plants produce AC: alternating current

- Reverses direction many times per second and is commonly sinusoidal $$V = V_0 \sin(2\pi ft) = V_0 \sin(\omega t)$$

- .$\omega$ = .$2\pi f$

- .$f$ is the frequency: number of complete oscillations per second

- Commonly .$\text{60 Hz}$ in NA

- Potential .$V$ oscillates between .$\pm V_0$, the peak voltage

- Current equation still works:

$$I = \frac{V}{R} = \frac{V_0}{R}\sin\omega t = I_0 \sin\omega t$$

- .$I_0 = V_0/R$ is the peak current

- Avg current is 0; it’s positive and negative for an equal amount of time

- Doesn’t mean that no heat is created or no power is needed

- Electrons are still moving though!

- Power is also consistent

$$P = I^2R = I_0^2 R \sin\omega t = \frac{V_0^2}{R} \sin\omega t$$

- Power is always positive because current is squared

- Since the .$\sin\dots$ oscillates between 1 and 0, the average power is $$\overline P = \frac{1}{2}I_0^2R = \frac{1}{2} \frac{V_0^2}{R}$$

- This can also be calculated by using the RMS values for .$I$ and .$V$ $$I_\text{rms} = \sqrt{\overline I^2} = \frac{I_0}{\sqrt{2}} \approx 0.707 I_0$$ $$V_\text{rms} = \sqrt{\overline V^2} = \frac{V_0}{\sqrt{2}} \approx 0.707 V_0$$ $$\dots \Longrightarrow \overline P = I_\text{rms} V_\text{rms} = I_\text{rms}^2 R = \frac{V_\text{rms}^2}{R}$$

- Fun fact: we can use the rms of a value to find the peak of it, e.x. $$V_0 = \sqrt{2} V_\text{rms}$$

- Keep in mind that this is the average power. Instantaneous power varies from .$0$ to .$2\overline P$

25.8 Microscopic View of Current #

- We’ve seen that electric current can be carried by negatively charged electrons in metal wires, and that in liquid solutions current can also be carried by positive and/or negatively charged ions

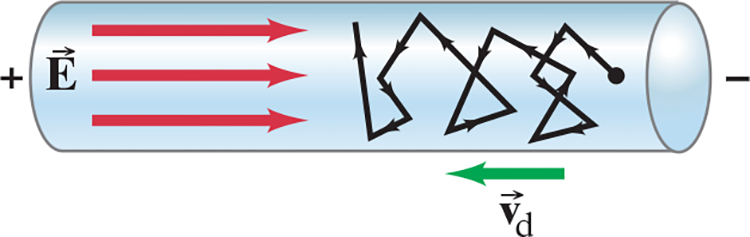

- When a potential difference is applied to the two ends of a wire, the direction of the electric field .$\vec E$ is parallel to the walls of the wire

- This field within the conducting wire does not contradict our earlier result that .$\vec E = 0$ inside a conductor in the electrostatic case, as we are no longer dealing with the static case.

- That is, charges are free to move in a conductor, and hence can move under the action of the electric field.

- If all the charges are at rest, then .$\vec E = 0$

- If all the charges are at rest, then .$\vec E = 0$

Current Density #

- Current density, .$\vec j$, is the current per area

$$j = \frac{I}{A} \Longrightarrow I = \int \vec j \cdot d \vec A$$

- .$I$ is the current through the whole surface

- .$d\vec A$ is an element of surface area over which the integration is taken

- Direction of the density is the same direction as .$\vec E$ – the direction that a positive charge would move

Drift Speed #

- Inside a wire, we can imagine the free electrons as moving about randomly at high speeds, bouncing off the metal atoms of the wire

- Somewhat like the molecules of a gas

- When an electric field exists in the wire the electrons feel a force and initially begin to accelerate but they soon reach a more or less steady average speed, known as their drift speed .$v_d$

- Collisions with atoms in the wire keep them from accelerating further

- The drift speed is normally very much smaller than the electrons’ average random speed inside the metal wire

Black zagged line represents the motion of an electron in a metal wire due to an electric field. The field .$\vec E$ gives electrons in random motion a net drift velocity .$\vec v_d$. Its direction (the net charge flow) is in the opposite direction of .$\vec E$ because electrons have a negative charge and .$\vec F = q \vec E$

- We can relate drift speed with the macroscopic view:

- In some time, the electrons travel (the average) distance .$l = v_d \Delta t$

- In that same time, electrons in volume .$V = Al = A v_d \Delta t$ pass through area .$A$ of the wire

- If there are .$n$ free electrons each of charge .$-e$ per unit volume, then the total electrons is .$N = nV$

- Thus, the charge is $$\Delta Q = \text{(number of charges, $N$)$\times$(charge per particle, $-e$)}$$ $$\dots = (nV)(-e) = -(nAv_d\Delta T)(e)$$

- We can then easily find the current (density): $$I = \frac{\Delta Q}{\Delta t} = -neAv_d$$ $$j = \frac{I}{A} = -nev_d$$

- Notice that the negative sign indicates that the direction of (positive) current flow is opposite to the drift speed of electrons.

Field inside a Wire #

- Voltage can be written in terms of microscopic values (in addition to the macro: .$V = IR$)

- Recall that resistance is related to density by .$R = \rho \frac{l}{A}$

- We can then write .$V$, .$I$ and .$j$ as

$$V = El = IR = (jA)\bigg(\rho \frac{l}{A}\bigg) = j \rho l$$

$$I = jA$$

$$j = \frac{1}{\rho}E = \sigma E$$

- .$\sigma$ is the conductivity of the wire

- .$\rho, \sigma$ do not vary with .$V$ and thus neither .$E$

- We can then write the microscopic statement of Ohm’s Law: $$\vec j = \sigma \vec E = \frac{\vec E}{\rho}$$

25.9 Superconductivity #

- At very low temperatures, the resistivity of certain metals and certain compounds or alloys becomes zero

- Materials in such a state are said to be superconducting

- In general, superconductors become superconducting only below a certain transition (critical) temperature, .$T_C$