15.1 Double Integrals over Rectangles #

- We describe closed rectangles in the form .$R = [a,b] \times [c,b] = \{(x,y) \in \mathbb{R}^2 \vert a \leq x \leq b, c \leq y \leq d\}$

- Then we can write the solid .$S$ that lies above .$R$ as .$S = \{(x,y,z) \in \mathbb{R}^3 \vert 0 \leq z \leq f(x,y), (x,y) \in R\}$

- To find the volume of this surface, we take a double integral $$V = \iint_R f(x,y)\ dA$$

Fubini’s Theorem: If .$f$ is continuous on the rectangle .$R = \{(x,y) \vert a \leq x \leq b, c \leq y \leq d\}$, then $$\iint_R f(x,y)\ dA = \int_a^b \int_c^d f(x,y)\ dy\ dx = \int_c^d \int_a^b f(x,y)\ dx\ dy$$ More generally, this is true if we assume that .$f$ is bounded on .$R$, .$f$ is discontinuous only on a finite number of smooth curves, and the iterated integrals exist.

Average Value #

- In the 2D case we could write the average as $$f_\text{avg} = \frac{1}{b-a} \int_a^b f(x) dx$$

- For 3D, instead of dividing by the change in just .$y$ (which was .$b-a$), we divide over the total area: $$f_\text{avg} = \frac{1}{A(R)}\iint_R f(x,y)\ dA$$

15.2 Double Integrals over General Regions #

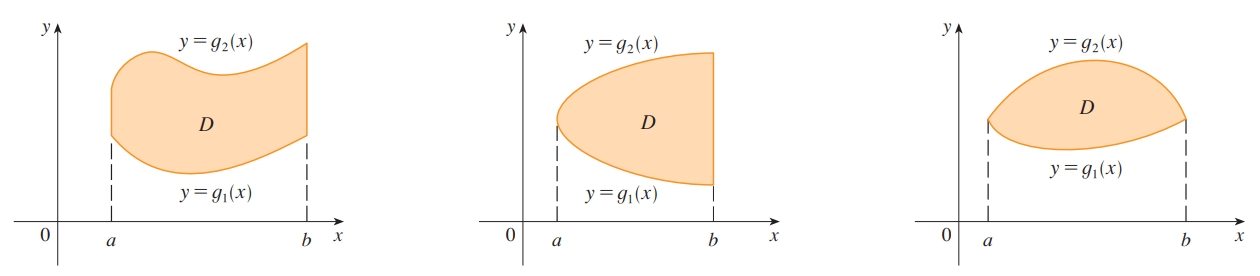

Type I #

If .$f$ is continuous on a type I region .$D$ such that $$D = \{(x,y)\ \vert\ a \leq x \leq b,\ g_1(x) \leq y \leq g_2(x)\ \}$$ then $$\int_D f(x,y)\ dA = \int_a^b \int_{g_1(x)}^{g_2(x)} f(x,y)\ dy\ dx$$

Type II #

If .$f$ is continuous on a type II region .$D$ such that $$D = \{(x,y)\ \vert\ c \leq y \leq d,\ h_1(y) \leq x \leq h_2(y)\ \}$$ then $$\int_D f(x,y)\ dA = \int_c^d \int_{h_1(y)}^{h_2(y)} f(x,y)\ dx\ dy$$

Properties of Double Integrals #

- $$\iint_D \Big[ f(x,y) + g(x,y)\Big]\ dA = \iint_{D} f(x,y)\ dA + \iint_{D} g(x,y)\ dA$$

- $$\iint_D c\cdot f(x,y)\ dA = c \iint_D f(x,y)\ dA\ \text{ where $c$ is a constant}$$

- $$\iint_D f(x,y)\ dA \geq \iint_D g(x,y)\ dA \ \text{ if $f(x,y) \geq g(x,y)$ for all $(x,y) \in D$}$$

- $$\iint_D f(x,y)\ dA = \iint_{D_1} f(x,y)\ dA + \iint_{D_2} f(x,y)\ dA\ \text{ for $D = D_1 \cup D_2$}$$

- $$mA(D) \leq \iint_D f(x,y)\ dA \leq MA(D)$$

- If .$m \leq f(x,y) \leq M$ for all .$(x,y) \in D$

15.3 Double Integrals in Polar Coordinates #

- Recall that we can convert cartesian to polar with the following equations:

$$r^2 = x^2 +y^2$$

$$x = r\cos\theta$$

$$y = r\sin\theta$$

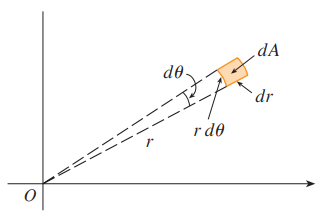

- We multiply .$r$ because an “infinitesimal” polar rectangle as an ordinary rectangle with dimensions .$r\ d\theta$ and .$dr$ and therefore has area .$dA = r\ dr\ d\theta$

- That is, the further out the polar rectangle is (the larger the .$r$), the larger the area of that rectangle is (this scale is .$\propto r$)

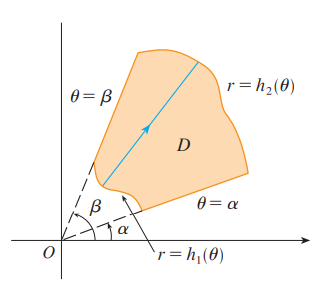

If .$f$ is continuous on a polar region of the form $$D = \{(r,\theta)\ \vert\ \alpha \leq \theta \leq \beta, h_1(\theta) \leq r \leq h_2(\theta) \}$$ then $$\iint_D f(x,y)\ dA = \int_\alpha^\beta \int_{h_1(\theta}^{h_2(\theta)} r \cdot f(r\cos\theta, r\sin\theta)\ dr\ d\theta$$

15.5 Surface Area #

The area of the surface with equation .$z = f(x,y), (x,y) \in D$, where .$f_x$ and .$f_y$ are continuous, is $$A(S) = \iint_D \sqrt{\big[f_x(x,y)\big]^2 + \big[f_y(x,y)\big]^2 + 1}\ dA$$

- Notice the similarities between the SA function and the line integral function, .$L = \int_a^b \sqrt{1 + \big( \frac{dy}{dx} \big)^2}\ dx$

15.6 Triple Integrals #

Fubini’s Theorem for Triple Integrals If f is continuous on the rectangular box B − fa, bg 3 fc, dg 3 fr, sg, then $$\iiint_B f(x,y,z)\ dV = \int_r^s\int_c^d\int_a^b f(x,y,z)\ dx\ dy\ dz$$

- The iterated integral on the right side of Fubini’s Theorem means that we integrate first with respect to .$x$ (keeping .$y$ and .$z$ fixed), then we integrate with respect to .$y$ (keeping .$z$ fixed), and finally we integrate with respect to .$z$.

- Note that if .$f$ is separable this just becomes the product of three single-dimensional integrals, or one two-dimensional integral and two one-dimensional integrals. Fubini’s theorem still applies.

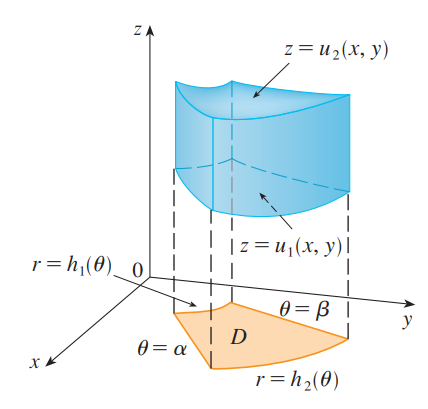

Type 1 #

$$\iiint_E f(x,y,z)\ dV$ = \iint_D \bigg[\int_{u_1(x,y)}^{u_2(x,y)}f(x,y,z)\ dz\bigg]\ dA$$

Type I #

$$\dots = \int_a^b \int_{g_1(x)}^{g_2(x)} \int_{u_1(x,y)}^{u_2(x,y)}f(x,y,z)\ dz\ dx\ dy$$

Type II #

$$\dots = \int_c^d \int_{h_1(y)}^{h_2(y)} \int_{u_1(x,y)}^{u_2(x,y)}f(x,y,z)\ dz\ dy\ dx$$

Type 2 #

$$\iiint_E f(x,y,z)\ dV$ = \iint_D \bigg[\int_{u_1(y,z)}^{u_2(y,z)}f(x,y,z)\ dx\bigg]\ dA$$

Type 3 #

$$\iiint_E f(x,y,z)\ dV$ = \iint_D \bigg[\int_{u_1(x,z)}^{u_2(x,z)}f(x,y,z)\ dy\bigg]\ dA$$

15.7 Triple Integrals in Cylindrical Coordinates #

Cylindrical to Cartesian #

$$x = r\cos\theta$$ $$y = r\sin\theta$$ $$z = z$$

Cartesian to Cylindrical #

$$r^2 = x^2 + y^2$$ $$\tan\theta = \frac{y}{x}$$ $$z = z$$

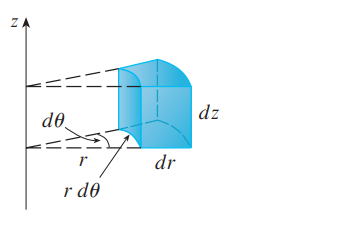

- Now we deal with integration in cylindrical coordinates.

- We have .$dV = dx\ dy\ dz$

- Since .$z$ is the same, .$dz$ is the same. However, we can convert .$dx, dy$ to .$r\ dr, dθ.$ since it is the same transformation as in polar coordinates.

- Thus the volume element in cylindrical coordinates is .$dV = r\ dr\ dθ\ dz$.

$$\dots = \int_\alpha^\beta \int_{h_1(\theta)}^{h_2(\theta)} \int_{u_1(r\cos\theta, r\sin\theta)}^{u_2(r\cos\theta, r\sin\theta)} f(r\cos\theta, r\sin\theta, z)\cdot r\ dz\ dr\ d\theta$$

15.8 Triple Integrals in Spherical Coordinates #

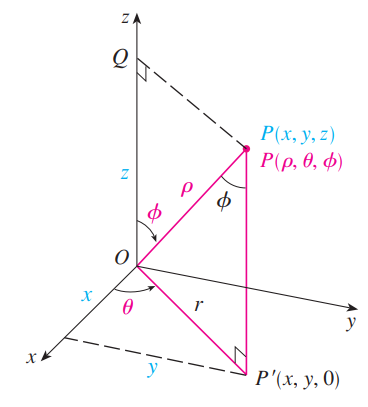

- Spherical Coordinates map .$(x,y,z) \Longrightarrow (\rho, \theta, \phi)$

- .$\rho$ is the distance between the origin and point; .$\rho \geq 0$

- .$\theta$ is the angle on the .$xy$ plane; .$\theta \in [0, 2\pi]$

- .$\phi$ is the angle between the .$z$ axis and the .$xy$ plane; .$\phi \in [0, \pi]$

- We only need to consider half the sphere; the other half is already counted by the varying .$\theta$.

Spherical to Cartesian #

$$x =\rho \sin \phi \cos \theta$$ $$y =\rho \sin \phi \sin \theta$$ $$z =\rho \cos \phi$$

Cylindrical to Spherical #

$$x =\rho \sin \phi$$ $$\theta = \theta$$ $$z =\rho \cos \phi$$

Cartesian to Spherical #

$$\rho = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + z^2}$$ $$\tan \theta = \frac{y}{x}$$ $$\tan \phi = \frac{z}{\sqrt{x^2 + y^2}}$$

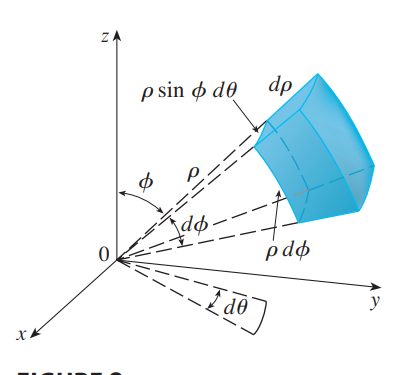

$$\iiint_E f(x,y,z)\ dV = \dots$$ $$\dots = \int_c^d \int_\alpha^\beta \int_a^b f(\rho\sin\phi\cos\theta, \rho\sin\phi\sin\theta, \rho\cos\phi) \cdot \rho^2 \sin\phi\ d\rho\ d\theta\ d\phi$$

- We have the volume element .$dV = dx\ dy\ dz$. By converting to cylindrical coordinates and doing some algebraic conversions we have .$dV = \rho^2 \sin\phi d\rho\ d\theta\ d\phi$:

15.9 Change of Variable in Multiple Integrals #

- We’ve done .$u$-sub before in single variable, as well as cartesian .$\iff$ polar .$\iff$ spherical in multivariable

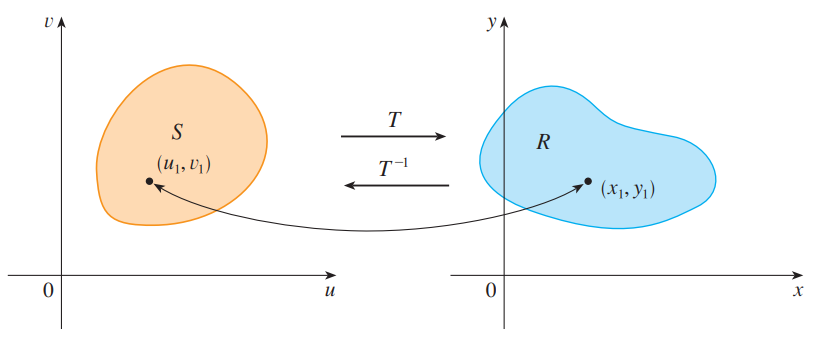

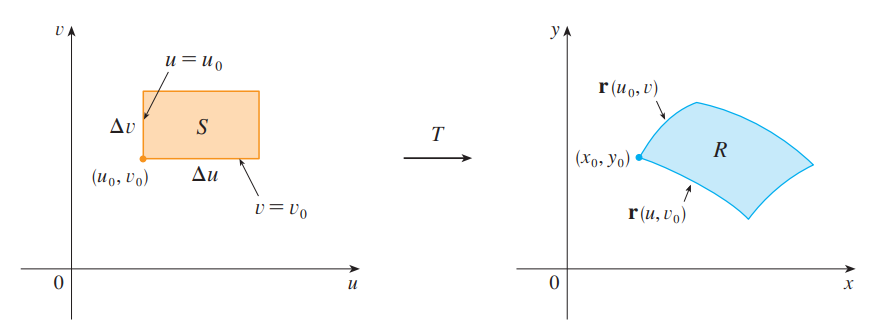

- More generally, we can consider a change of variables that is given by a transformation .$T$ from the .$uv$-plane to the .$xy$-plane:

- .$T(u,v) = (x,y)$ where .$x = g(u,v), y = h(u,v)$

- .$x,y$ must be differentiable in .$S$

- We usually assume that .$T$ is a .$C^1$ transformation: .$g$ and .$h$ have continuous first-order partial derivatives

- A transformation .$T$ is really just a function whose domain and range are both subsets of .$\mathbb{R}^2$

- If .$T(u_1, v_1 = (x_1, y_1)$, then the point .$(x_1,y_1)$ is called the image of the point .$(u_1, v_1)$

- That is, .$T$ transforms .$S$ into a region .$R$ in the .$xy$-plane called the image of .$S$, consisting of the images of all points in .$S$

- If no two points have the same image, .$T$ is called one-to-one (

wiki)

- If .$T$ is a one-to-one transformation, then it has an inverse transformation .$T^{-1}$ from the .$xy$-plane to the .$uv$-plane + it may be possible to solve for .$u$ and .$v$ in terms of .$x$ and .$y$: .$u = G(x,y), v = H(x,y)$

- If not one-to-one, then the transformation would “fold” over itself – we would double-count some amount of area

- .$T(u,v) = (x,y)$ where .$x = g(u,v), y = h(u,v)$

- This change in variable affects the size of the region (the area/integral)

- The vector .$\vec r (u, v) = g(u, v) \hat i + h(u, v) \hat j$ is the position vector of the image of the point .$(u, v)$.

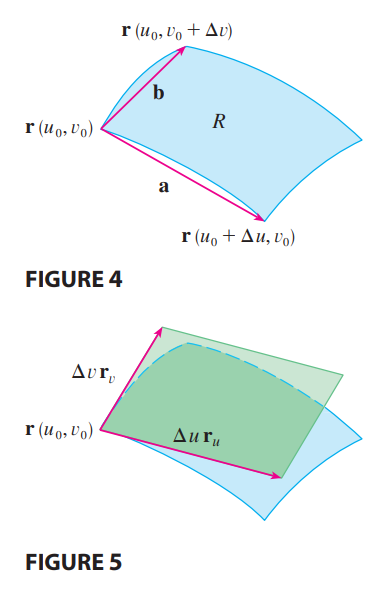

- The tangent vector at .$(x_0, y_0)$ to the image curve of the lower side (.$v = v_0$) of .$S$: $$\vec r_v = \frac{\delta x}{\delta v} \hat i + \frac{\delta y}{\delta v} \hat j$$

- Similarly, the tangent vector at .$(x_0, y_0)$ to the image curve of the left side (.$u = u_0$) of .$S$: $$\vec r_u = \frac{\delta x}{\delta u} \hat i + \frac{\delta y}{\delta u} \hat j$$

- The vector .$\vec r (u, v) = g(u, v) \hat i + h(u, v) \hat j$ is the position vector of the image of the point .$(u, v)$.

- We can then find the area by calculating the cross product: $$\vec r_u \times \vec r_v = \begin{vmatrix} \frac{\delta x}{\delta u} & \frac{\delta x}{\delta v} \\ \frac{\delta y}{\delta u} & \frac{\delta y}{\delta v} \end{vmatrix}$$ $$\dots = \frac{\delta (x,y)}{\delta (u,v)} = \frac{\delta x}{\delta u} \frac{\delta y}{\delta v} - \frac{\delta x}{\delta v}\frac{\delta y}{\delta u}$$

- This is the Jacobian of the transformation .$T$ given by .$x = g(u,v)$ and .$y = h(u,v)$

Formally, Suppose that .$T$ is a .$C^1$ transformation whose Jacobian is nonzero and that .$T$ maps a region .$S$ in the .$uv$-plane onto a region .$R$ in the .$xy$-plane. Suppose that .$f$ is continuous on .$R$ and that .$R$ and .$S$ are type I or type II plane regions. Suppose also that .$T$ is one-to-one, except perhaps on the boundary of .$S$. Then, $$\iint_R f(x,y) dA = \iint_S f(x(u,v), y(u,v)) \Bigg\vert \frac{\delta (x,y)}{\delta (u,v)} \Bigg\vert\ du\ dv$$

- That is, .$dA = \Bigg\vert \frac{\delta (x,y)}{\delta (u,v)} \Bigg\vert\ du\ dv$

General Solving Steps #

- Write down transformations (.$x$ and .$y$ in terms of .$u$ and .$v$)

- Find the Jacobian

- Rewrite the equations with .$u$ and .$v$

- Sketch the new region + find new bounds

- Integrate on the new field with Jacobian

Triple Integrals #

- We can also let .$T$ be a transformation that maps a region .$S$ in .$uvw$-space onto a region .$R$ in .$xyz$-space by means of the equations:

$$x = g(u,v,w)$$

$$y = h(u,v,w)$$

$$z = k(u,v,w)$$

- Then, the Jacobian is a .$3 \times 3$ determinant: $$ \frac{\delta (x,y,z)}{\delta (u,v,w)} = \begin{vmatrix} \frac{\delta x}{\delta u} & \frac{\delta x}{\delta v} & \frac{\delta x}{\delta w} \\ \frac{\delta y}{\delta u} & \frac{\delta y}{\delta v} & \frac{\delta y}{\delta w} \\ \frac{\delta z}{\delta u} & \frac{\delta z}{\delta v} & \frac{\delta z}{\delta w} \end{vmatrix} = dA$$