20.1 Intro #

- Second law states that systems only increase in entropy over time

- That is, most systems are on directional

- E.x. mixing salt and pepper together result in an mixture. No matter how much you keep mixing it, they won’t naturally separate and return to the initial state even though it follows first law of thermo (conserving energy)

- (Specific) Second Law of Thermo

Heat can flow spontaneously from a hot object to a cold object; heat will not flow spontaneously from a cold object to a hot object.

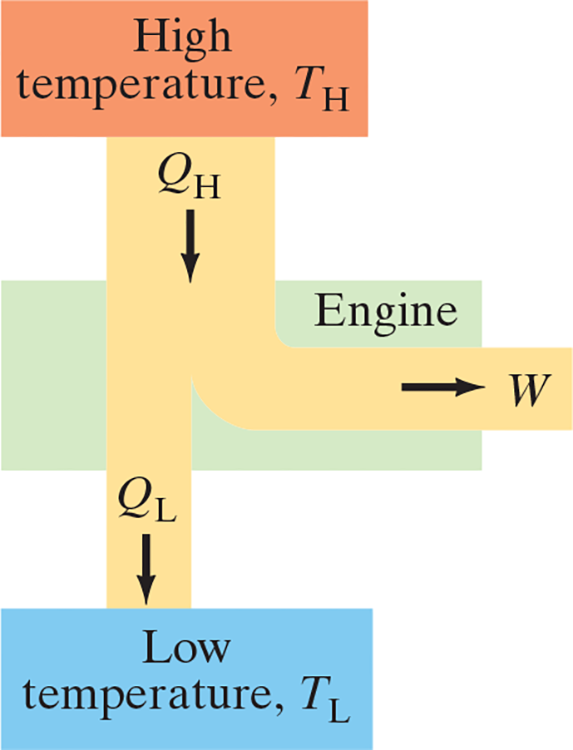

20.2 Heat Engines #

- Heat Engine: Any device that changes thermal energy into mechanical work, such as steam or car engine

- Show importance in developing the second law of thermo

- Mechanical energy can only be obtained from thermal energy when heat is allowed to flow from high temp to low temp

- During this process, some of the heat can be transformed to mechanical work

- Heat engines run in a repeating cycle: the system returns repeatedly to its starting point and thus can run continuously

- In each cycle .$\Delta E_{\text{int}} = 0$ because it returns to the initial state

- Thus, heat input .$Q_H$ at a .$T_H$ is partly transformed into work .$W$ and partly exhausted as heat .$Q_L$ at .$T_L$

- By conservation of energy, .$Q_H = W+Q_L$.

- Operating Temperatures: The high and low temperatures, .$T_H, T_L$

- .$Q_H, Q_L, W > 0$

- Change in temperature is required for a change in pressure

- Gas exhaust is cooled to a lower temperature and condensed so that the exhaust pressure is less than intake pressure

- Thus, the work the piston must do on the gas to expel it is less than the work done by the gas on the piston during the intake

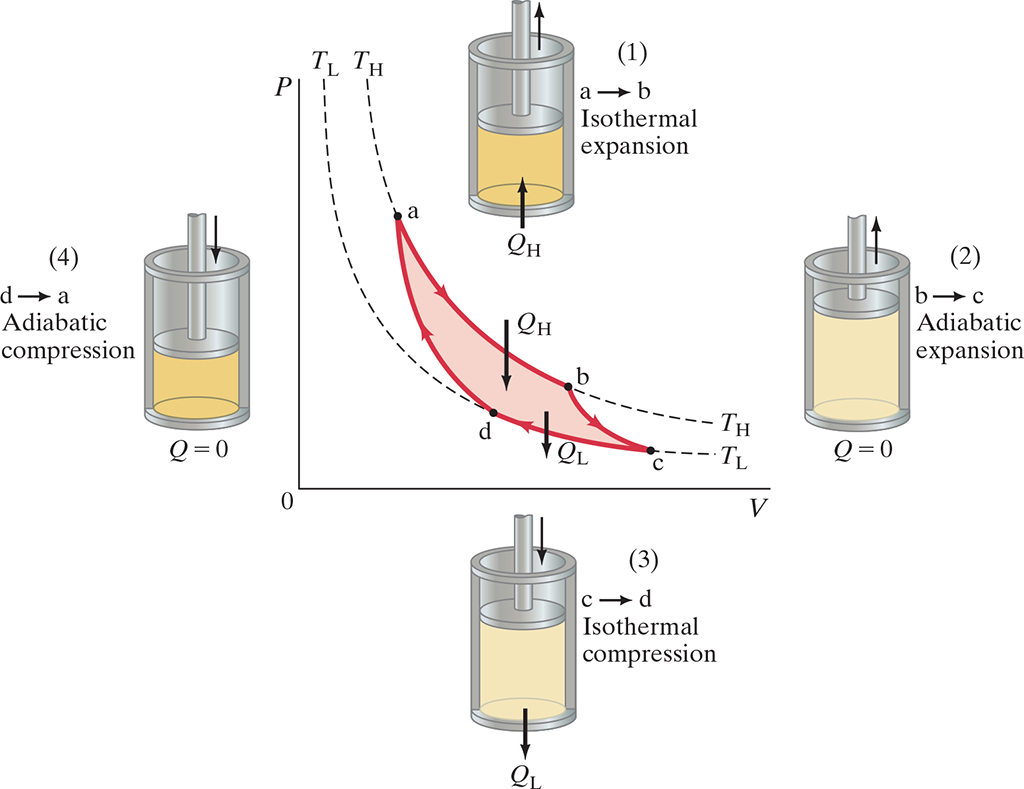

20.3 (Ir)reversible Processes; Carnot Engine #

- Carnot engine is ideal: doesn’t take into account turbulence in gas, friction, etc.

- Consist of four processes done in a cycle

- Isothermal expansion (.$\Delta T = 0$) with the addition of heat .$Q_H$ along path .$ab$ at temperature .$T_H$

- Adiabatic expansion (.$Q = 0$) lowering temperature to .$T_L$ along path .$bc$

- Isothermal compression (.$\Delta T = 0$) leads to heat .$Q_L$ flowing out along path .$cd$

- Adiabatic compression (.$Q = 0$) occurs path .$da$, returning to temperature .$T_H$

- Each process is reversible; that is, each occurs infinitely slowly so that the process could be considered a series of equilibrium states

- Real processes are irreversible

- Work done in a cycle is proportional to area enclosed by the curve representing the cycle on a .$PV$ diagram (.$abcd$)

- Efficiency is given by .$e = 1-\frac{Q_L}{Q_H} \Longrightarrow e_{\text{ideal}} = 1 - \frac{T_L}{T_H}$

- Carnot’s Theorem:

All reversible engines operating between the same two constant temperatures .$T_H$ and .$T_L$ have the same efficiency. Any irreversible engine operating between the same two fixed temperatures will have an efficiency less than this.

- Only at absolute zero would 100% efficiency be reachable. But getting to absolute zero is a practical (as well as theoretical) impossibility

- Kelvin-Planck statement of the second law of thermodynamics:

no device is possible whose sole effect is to transform a given amount of heat completely into work.

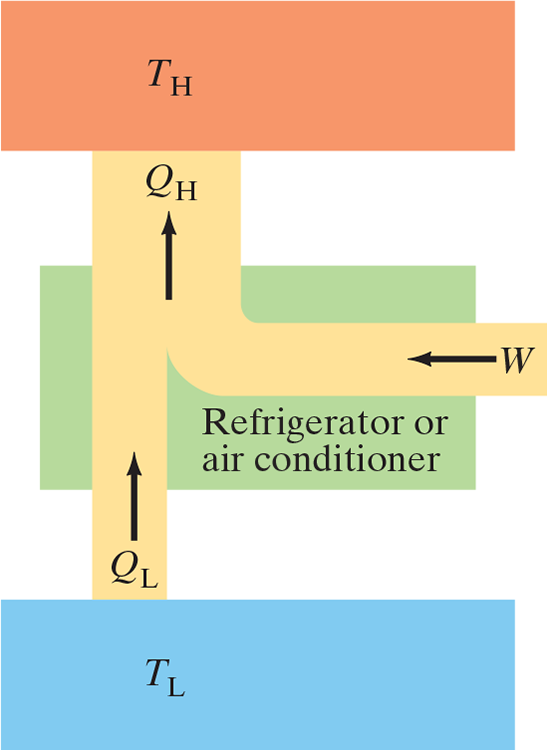

20.4 Refrigerators, AC, Heat Pumps #

- Refrigerators, air conditioners, and heat pumps are just the reverse of heat engines

- Each transfer heat ouf of a cool environments into a warm environment

- A perfect fridge (no work required to take heat from low temp to high temp) is impossible

No device is possible whose sole effect is to transfer heat from one region at a temperature .$T_L$ into a second region at a higher temperature .$T_H$ (Clausius statement)

Coefficient of Performance (COP): .$\text{COP} = \frac{Q_L}{W}$

- The more heat .$Q_L$ removed from a fridge for a given amount of work, the more efficient it is

- Energy is conserved, so we can write .$Q_L + W = Q_H$ or .$W = Q_H-Q_L$

- We can then write .$\text{COP} = \frac{Q_L}{W} = \frac{Q_L}{Q_H-Q_L} \Longrightarrow \text{COP}_{\text{ideal}} = \frac{T_L}{T_H-T_L}$

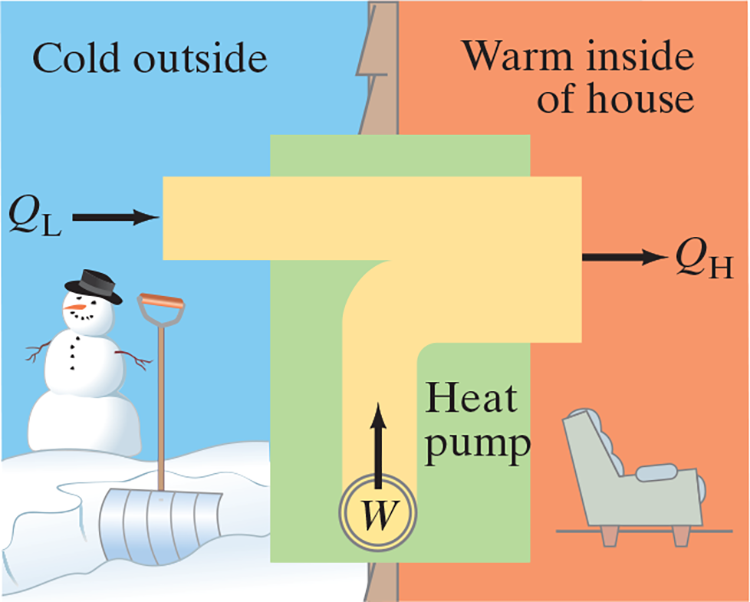

Heat pump

- Electric motor does work .$W$ to take heat .$Q_L$ from outside at low temperature and delivers heat .$Q_H$ to inside at a hot temperature

- Whereas fridges cool (remove .$Q_L$), heat pumps heat (deliver .$Q_H$)

- Thus, COP uses .$Q_H$ instead of .$Q_L$: .$\text{COP} = \frac{Q_H}{W}$

- COP is greater than 1 because .$W+Q_L = Q_H$

20.5 Entropy #

- Entropy, unlike heat, is a state variable and measures the (dis)order of a system

- When heat is added to a system by a reversible process then change in entropy is $$\Delta S = \frac{Q}{T} \ \ \text{[Constant T]} \Longrightarrow dS = \frac{dQ}{T} \ \ \text{[Non-const T]}$$

- The change of entropy between two states doesn’t depend on the process. Thus, $$\Delta S = S_b - S_a = \int_a^b dS = \int_a^b \frac{dQ}{T}$$

20.6 Entropy and Second Law #

- In an isolated system with two objects that eventually reach equilibrium, we can write the change (increase) in entropy as $$\Delta S = \Delta S_H + \Delta S_L = - \frac{Q}{T_{HM}} + \frac{Q}{T_{LM}}$$

- .$T_{HM}$ is the average temperature between .$T_H$ and .$T_M$ where .$T_M$ is the average between .$T_H$ and .$T_L$

- E.x. if .$T_H = 0^\circ C, T_L = 0^\circ C$, then .$T_M = 4^\circ C$ so .$T_{HM} = 6^\circ C$ and .$T_{LM} = 2^\circ C$. Also, we use .$Q = mc \Delta T$ to find heat and use half .$T_{M}$ (in this case .$4^\circ C$) for .$\Delta T$

- Since .$T_{HM} > T_{LM}, \Delta S > 0$ is always true

- While one system may decrease in entropy, the other one always increases more so net always increases

- For adiabatic processes, we know .$dQ = dW = P dV$, thus $$\Delta S_\text{gas} = \int \frac{dQ}{T} = \frac{1}{T} \int_{V_1}^{V_2} P\ dV$$ and since we know through the idea gas law that .$P = nRT/V$ so $$…= \frac{1}{T} \int_{V_1}^{V_2} \frac{nRT}{V}\ dV = nR \ \ln \bigg(\frac{V_2}{V_1}\bigg)$$

20.7 Order to Disorder (not covered) #

- If we say that entropy is a measure of (dis)order in a system, we can write the second law as

Natural processes tend to move toward a state of greater disorder

- When ice melts to water at 0°C, the entropy of the water increases.

- Intuitively, we can think of solid water, ice, as being more ordered than the less orderly fluid state which can flow all over the place.

- This change from order to disorder can be seen more clearly from the molecular point of view: the orderly arrangement of water molecules in an ice crystal has changed to the disorderly and somewhat random motion of the molecules in the fluid state.

- When a hot substance is put in contact with a cold substance, heat flows from the high temperature to the low until the two substances reach the same intermediate temperature.

- At the beginning of the process we can distinguish two classes of molecules: those with a high average kinetic energy (the hot object), and those with a low average kinetic energy (the cooler object).

- After the process in which heat flows, all the molecules are in one class with the same average kinetic energy; we no longer have the more orderly arrangement of molecules in two classes – Order has gone to disorder

- Furthermore, the separate hot and cold objects could serve as the hot and cold-temperature regions of a heat engine, and thus could be used to obtain useful work. But once the two objects are put in contact and reach the same temperature, no work can be obtained.

- Disorder has increased, because a system that has the ability to perform work must surely be considered to have a higher order than a system no longer able to do work.

- When a stone falls to the ground, its macroscopic kinetic energy is transformed to thermal energy.

- Thermal energy is associated with the disorderly random motion of molecules, but the molecules in the falling stone all have the same velocity downward in addition to their own random velocities.

- Thus, the more orderly kinetic energy of the stone as a whole (which could do useful work) is changed to disordered thermal energy when the stone strikes the ground. Disorder increases in this process, as it does in all processes that occur in nature.

20.8 Unavailability of Energy; Heat Death (not covered) #

In any natural process, some energy becomes unavailable to do useful work

- That is, as time goes on, both energy is degraded and entropy increases

- A rock that falls to the ground could instead used it’s energy towards useful work versus exerting kinetic/thermal energy while falling

- Two separate hot and cold objects could serves as the high and low temperature regions for a heat engine (obtaining useful work). Instead, if the tow objects are put in contact with one another, they’ll eventually reach the same uniform temperature and not be able to do any work.

- Heat Death: All energy of the universe degrades into thermal energy

- Very far out

- Scientists are unsure whether this is inevitable or whether we can even extrapolate the 2nd law to the scale of our universe

20.9 Statistical Interpretation of Entropy/2nd (not covered) #

- We can only realistically observe macrostates and not microstates

- However, we can make inferences about microstates with probabilities

- Each microstate is equally probable of occurring

- Thus, the number of microstates that give the same macrostate correspond to the relative probability of that macrostate occurring

- The most probable state of a gas is one in which the molecules take up the whole spaces and move about randomly (in a maxwell distribution)

- At the same time, the very orderly arrangement of all molecules located in one corner of the room and all moving with the same velocity is extremely unlikely

- Therefore, the probability is directly related to the disorder and hence entropy of the system

- The most probably state is the one with greatest entropy or greatest disorder and randomness

- It’s also the macrostate that corresponds to the most microstates

- The netropy of a system in a given macro state can be written as: $$ S = k \ \ln\mathscr{W}$$

- .$k$ is the Boltzmann’s constant and .$\mathscr{W}$ is the number of microstates corresponding to the given macrostate

- That is, .$\mathscr{W}$ is proportional to the probability of occurrence of that state

- .$\mathscr{W}$ is also called the thermodynamic probability or the disorder parameter

20.10 Thermo Temperature; Third Law (not covered) #

- Ideal Carnot Cycles always have the ratio $$\frac{Q_L}{Q_H} = \frac{T_L}{T_H}$$

- Note that this relation doesn’t depend on the working substance, thus it can server as the basis for the Kelvin scale

- The closer a temperature is to abs zero, the more difficult it is to reduce the temp further

- Third Law:

It is not possible to reach absolute zero in any finite number of processes

- Thus, since .$e = 1 - \frac{T_L}{T_H}$ and because .$T_L$ can’t ever be zero then 100% efficiency is never possible